Can following 'The Bachelor' lead to mistrust of all media?

One cranky TV critic's screed suggesting how reality TV might feed mistrust of all media.

Those who know me and my work know that I have a burning hatred for most programs known as “reality TV.” But it wasn’t until this week, that I began to connect the popularity of that form to some of the other problems we’ve been having with trust in media and agreement on basic facts.

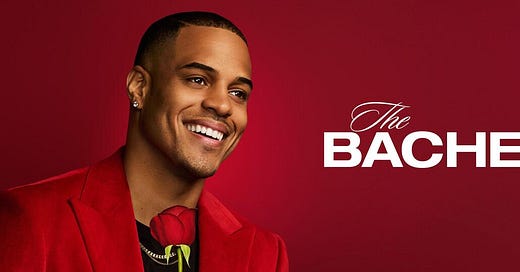

Bear with me a moment. My thoughts turned to this subject when I saw reports the showrunners for ABC’s The Bachelor were leaving the franchise. These were two of the three executive producers who basically went mute for eight seconds last year, when I asked them why the show has struggled with so many race-based controversies. (for a recap of that moment and my thoughts about it back then, peep this NPR story.)

Of course, I’ve always felt the real reason why leaders of the show can’t talk frankly about The Bachelor’s problems with race, is because the series is committed to existing inside a fantasy world which avoids and ignores all such subjects. So they are constantly lurching into controversies connected to race, like drunk people trying to walk across a dark field littered with rakes.

So-called “reality TV” shows are a unique animal in media. Their premise – featuring people who are not professional performers placed in manufactured situations to create real emotions – has been degraded by success into something else.

Long-running shows with loads of viewers like The Bachelor can never leave it to chance that a given season will have the emotional highs and lows needed to keep fans satisfied. So there is mounting pressure at every stage of the production to manipulate circumstances to ensure that every episode and each season is an entertaining as possible.

After more than two decades, viewers watch these shows believing they are in on the con. They know producers manipulate contestants and circumstances, and they know many participants aren’t honest about why they are doing the show or what choices they make in the competition.

Yet they want to believe they are seeing something real. And they are encouraged to feel that way by participants and producers who will not fully admit what they do to make the show’s storylines happen. And it is this dissonance – viewers watching something they know is fake, wanting to believe it and yet knowing they cannot trust what those who make it are telling them – that leads to a crushing cynicism about the whole enterprise.

And this dynamic has spread to other parts of the unscripted world. Meghan Markle (or Meghan Sussex, as she has recently asked to be called) is currently getting pilloried for a boring show she’s created for Netflix where she makes lunch for friends and tries to present herself as a down-to-earth stay-at-home mom.

But she is doing all this in a location that doesn’t seem to be her home, with celebrity friends like TV star Mindy Kaling. It’s a show where she talks often about being a mom but doesn’t interact with her children or her husband. It is tough to know what she’s trying to do – offer a new type of lifestyle branding or soften her image with a relentlessly inoffensive program – producing a dissonance which feels deafening.

Ditto with another unscripted show recently on TLC, The Baldwins, featuring actor Alec Baldwin, his wife Hilaria and their seven (!) young children. The show’s initial episodes were filmed last year as Baldwin was preparing to go on trial for manslaughter charges in the death of cinematographer Halyna Hutchins -- so footage veered from scenes of Alec Baldwin as the befuddled dad, trying to keep up with his young brood, and moments when he spoke gravely of the crisis hanging over the family. (a judge eventually threw out the charges against Alec Baldwin last July.)

Viewers likely couldn’t help wondering: Why is he opening up his home to cameras now? Money? Improving his image? If they feel, as they say several times on camera, that Hutchins’ family is going through a much worse loss, why do Alec and Hilaria spend so much more time talking about what they are going through? And why do they rarely show the nannies and household help who must be aiding this wealthy family in keeping up with their children?

(I talked about both With Love, Meghan and The Baldwins on the midday show Here and Now a bit ago. Listen here.)

Too many “reality TV”-style shows have lying to the audience baked into their structure, blurring the line between documentary projects which are expected to have the transparency and accuracy of journalism, and fictional creations which take all kinds of liberties to tell a story.

And maybe it’s just an old-fashioned critic feeling particularly persnickety. But I can’t help wondering if the dissonance that lead audiences to distrust what they see on reality TV shows seeps into all the media they consume.

A commenter on an early version of this column made an astute observation: This connects to how NBC’s reality TV competition The Apprentice fed the false notion that Donald Trump was a super-successful leader and businessman, giving him the pop cultural platform on which to build his presidential candidacy.

No one says it better than Emily Nussbaum, who I quoted in my review for the New York Times of her wonderful book, Cue the Sun! The Invention of Reality TV. “Taking a failed tycoon who was heavily in hock and too risky for almost any bank to lend to,” Nussbaum writes, “a crude, impulsive, bigoted, multiply-bankrupt ignoramus, a sexual predator so reckless he openly harassed women on his show, then finding a way to make him look attractive enough to elect as president of the United States? That was a coup, even if no one could brag about it.”

For many years, I have been cautioning audiences in presentations and personally to be careful about how they consume cable TV news, which is designed to provoke and alarm, whether its the right-wing propaganda of Fox News Channel or more centrist reporting of CNN. Exposure to hours and hours of this programming can lead people to feel stressed, have an overly alarmist view of crime levels and personal danger and become more politically polarized— so what if that dynamic extends to the impact of watching reality TV?

Good friends have passed along suspicions that the last election was somehow rigged. Before that, I heard murmurs that the first assassination attempt against Donald Trump last year was somehow staged. Real life disbelief in the power of vaccines feels like being trapped in a movie where the hero finds the cure to a deadly contagion, but no one will actually take it.

I’m not saying all that can be traced to reality TV-inspired media cynicism, of course. But it may be a factor – one more straw on the camel’s back to weigh down an audience so buffeted by information it cannot trust, it is easier to grab for what feels true, regardless of where they find it.

And the elephant in the room, quite literally, is to ask:

How much of this problem started with The Apprentice?

This is such a good point that I will never be able to unsee.