Forgetting Hurricane Katrina's lessons on its 20th anniversary

America's amnesia about the impact of race and poverty in Katrina's aftermath shows how our refusal to learn from history is crippling our present

The first thing I noticed was the cars.

Dozens and dozens of them, dusty and clearly not driveable, lined up beneath overpasses and tucked into corner across the city. It was as if everyone in New Orleans showed up for the same football game five months earlier and took an Uber home, leaving whatever they came in wherever they parked it.

This was five months after Hurricane Katrina brought the worst humanitarian disaster to New Orleans the area had seen in generations. I had come to the city focused on documenting how the struggle of staffers at the local newspaper, The Times-Picayune, might mirror the struggle of the city itself to recover from a storm and catastrophic flooding that killed nearly 2,000 people, brought billions in damages and produced a weeklong odyssey of misery for those who couldn’t evacuate which was documented by TV reporters for a global audience.

What I was learning: In too many ways, recovery was so slow it was as if the storm had happened yesterday. A house unmoored from its foundations and washed into the middle of the street in a tony neighborhood still stood there. One iconic image from the storm’s aftermath showed a small school bus crushed underneath a giant barge; when I got to the city months later, it was still there.

As I walked through the lower Ninth Ward, strolling through a grassy field, my foot caught on something; I realized it was the exposed pipe which once connected to a toilet in a home. The house had been erased so completely, it seemed like the pipe had sprouted up out of nowhere. And when I walked up to the front door of the newspaper’s then-editor, I told him he had forgotten his groceries in the car parked in front of his house. Turns out, that wasn’t his car, it had been sitting there since the storm and repeated calls to the city produced no result.

I was astonished and angry to see a major American city, abandoned in real time months ago, remaining neglected months later. Twenty years later, as I watch a spate of documentaries commemorating this awful anniversary, the anger returns with a deeper regret about my countrymen.

We rarely remember the lessons taught us by history and devastating experience.

Netflix’s Katrina: Come Hell and High Water offers a poignant portrait of the culture, especially in the city’s Black neighborhoods, which got erased by the flood’s devastation. Bad as it was, the storm itself wasn’t the biggest problem for New Orleans, but the massive flooding that followed -- inundating a city which sits many feet below sea level. This docuseries walks viewers through the horror, frustration, sorrow and fear of the storm and its aftermath, weaving together an evocative mix of archival footage and new interviews.

(The full first episode of NatGeo’s series.)

NatGeo’s five-part program Hurricane Katrina: Race Against Time digs into the misinformation and stereotypes which helped deter first responders and emergency workers from helping to evacuate residents stuck at New Orleans’ Superdome and Convention Center after the storm with little food, water or acceptable facilities. The city’s former police superintendent is shown admitting he mistakenly passed along false information about snipers targeting emergency workers – the program quotes others suggesting people were shooting in the air when helicopters approached to get their attention and show they were alive.

The program showed how federal officials responsible for getting aid the city stayed in distant Baton Rouge, unaware of how bad conditions were getting in the aftermath of the storm. And prejudices about poor people and Black people resulted in groups of vigilantes keeping desperate folks from leaving those areas to find food and water in neighboring communities.

(I got to moderate a panel with other TV critics, director Traci Curry and showrunner Myles Estey.)

But what made me most angry watching these two documentaries is the sense of how little we have remembered about the lessons from that calamity. At the time, media outlets howled about the way poor people, largely black, were forced to hunker down in New Orleans and weather a nightmarish storm, endure horrific conditions as flooding isolated those who stayed in town and the government fumbled delivering aid.

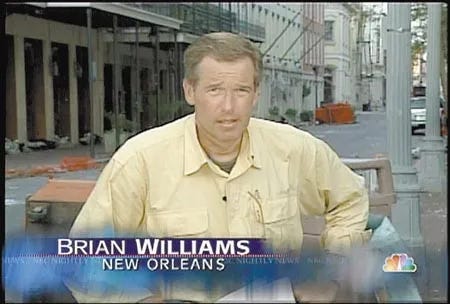

Brian Williams, then anchor of the NBC Nightly News, rode out the storm in the Superdome and kept reporting from the city as it drowned in floodwaters and misery. Before controversy over his hyperbole about what he saw there cut short his time at Nightly News, Williams assured me: “If this does not spark a national discussion on class, race, the environment, oil, Iraq, infrastructure and urban planning, I think we’ve failed…We’re going to be talking about this, in some way, for the rest of my lifetime and yours.”

I wrote a story for the then-St. Petersburg Times (now called the Tampa Bay Times) six months after Katrina’s aftermath, noting that the discussion Williams expected never really happened. On the storm’s fifth anniversary, as I noted in my book Race-Baiter, Williams set a lot of blame with his audience, telling me, “it’s a lot easier to watch Entourage.”

In that 2006 St. Petersburg Times story, I quoted Jane Knitzer, director of the National Center for Children in Poverty, a nonpartisan think tank: "Americans don't like to talk about poverty. And if they do talk about it, they like to see it as an individual problem, not a structural problem. It's kind of blaming the victim and not looking at what happens when you make policy choices which privilege the wealthy."

We are now living that reality in so many ways. As diversity programs are dismantled, poverty programs are defunded, more humane anti-crime initiatives are discarded in favor of allowing the military to police streets in large American cities, we have forgotten the lessons of our history. Perhaps because we’d rather watch Real Housewives and insist, absent any proof, that these measures make some kind of twisted sense.

As we all watch the long parade of Katrina documentaries marking the storm’s 20th anniversary, the best way we can honor those who lost so much in that tragedy is to refuse to forget its lessons. Chief among them: poverty is not a choice or a sign of inferior culture, so it is our most important duty to help lift up those who have less, so when disaster strikes, they are more likely to survive it.

The other lesson of Katrina: prejudice, stereotypes and misinformation kills – especially in an emergency. Those who can cut through the fog of an emergency to tell people accurately what is happening, what is needed and who is in danger – fact-based journalists, reporting without fear or favor – are more important than ever.

Thank you for avoiding the resiliency bullshit. You’ve told it like it was, and still is, and the failures to confront the real issues.

Thank you for this.